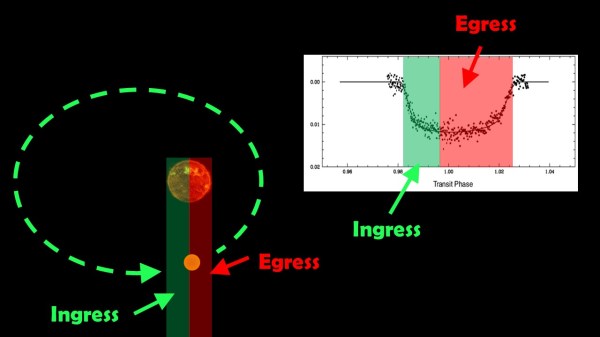

If you’ve ever heard about a new exoplanet being discovered, it was most likely found using the transit method. Astronomers continuously monitor the brightness of a star over time using telescopes equipped with sensitive photometers to detect any small changes in the star’s light. When an exoplanet passes, or “transits,” in front of its host star from our viewpoint, it causes a slight but measurable dimming of the star’s light. This dip in brightness occurs because the planet blocks a portion of the starlight.

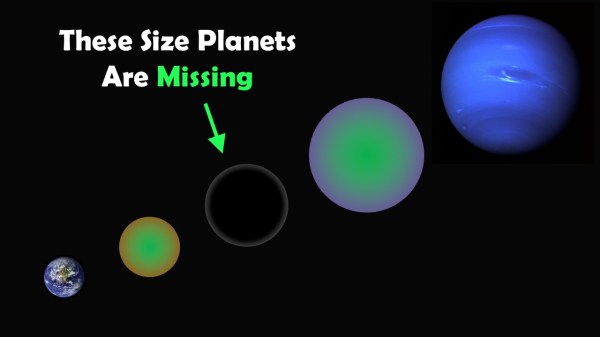

Quite straightforward, right? However, did you know that the transits often show variations from transit to transit, i.e. they aren’t always the same length, depth (how much light is blocked out), time or even symmetric. Below are a range of videos that explain how additional unseen exoplanets, exomoons, orbital parameters and even how the changing relative orientation of exoplanets orbit can alter the transit.